What are the common causes of falls with people living with dementia?

What are the common causes of falls with people living with dementia?

By researching and understanding the various causes of falls, this can increase awareness and hopefully prevent certain falls from happening. If a fall does occur, then an analysis of the situation can help determine what may have triggered the fall and potentially prevent another from happening.

It’s also important to assess and pick up your loved one using safe lifting equipment, such as the Mangar Camel to prevent the long-term damaging effects of long lie occurring. This proactive approach to fall prevention and post-fall management are important aspects of providing quality care for adults living with dementia.

Falls prevention begins with understanding the common causes of falls with people living with Alzheimer’s and dementia;

Physical weakness due to lack of exercise

Research has suggested that a decline in gait or balance can be an early indictor of a decline in cognition. As Alzheimer’s progresses into the middle stages and later stages, it causes a decline in muscle strength, walking and balance.

The benefits of physical exercise in dementia are many and can include increased daily functioning and improved cognition.

You can read more about the benefits of exercise and recommended activities here (links to falls and dementia article)

Memory impairment

With the progression of Alzheimer’s, keeping your loved one from falling can become increasingly difficult because of the cognitive decline associated with the disease.

For example, you may need to explain to your loved one that they should not get up out of their chair because they are no longer strong or steady enough to do so. This can be a difficult change. As their memory is impaired, they may continually try to walk independently when it is not safe to do.

Visual-Spatial Problems

Alzheimer’s and dementia can affect visuospatial abilities and therefore a person can misinterpret what they see, for example, misjudging steps and uneven terrain.

It is recommended to have their vision checked regularly, as eyesight can decline as you get older. For example, poor vision could prevent them from seeing a trip hazard which could cause them to fall.

Another example of a potential trip hazard is when a home is full of too much clutter. Occasionally some people living with dementia develop the tendency to want to hoard things.

Fatigue

It is common for falls to take place in the evening before they go to bed. This is due to fatigue and becoming more tired and weary throughout the day.

Medication Side Effects

There are some medications that can increase the risk of falls due to their side effects. Antipsychotic medications, for example, can sometimes have a side effect of orthostatic hypotension, which is when a person can experience a sudden drop in blood pressure if they stand up too quickly.

Medications that facilitate sleep can cause drowsiness and medications that work to lower blood pressure can causes dizziness, both increasing the chance of a fall.

Falls & Dementia

Falls can be an inevitable part of living with dementia, as it is associated with an ongoing decline of the brain and its abilities. The risk factors of falling are greater as the condition incurs problems with mobility, balance, and muscle decline. People living with dementia often find difficulties with processing what they see and how to react to situations. The use of medication may also cause effects such as drowsiness, dizziness and lower blood pressure which may in turn cause a fall.

If someone living with the condition is having issues with their mobility, then it is important to remain physically active and get the right support. Staying physically active has shown to help delay and reduce some mobility problems associated with dementia.

Some people with dementia may have participated in regular exercise over the years whilst others might have exercised very little. It is important to take into consideration the age, type of dementia the person has and their abilities when deciding which physical exercise is best to partake in.

We would recommend those who have not taken part in regular exercise for some time and those with other health issues to seek medical advice. Whether it is through a GP, physiotherapist, or other healthcare professional before beginning a new form of physical activity.

It is important to choose activities that are suitable for the person and that they find enjoyable. Exercise can be done individually, with one-to-one supervision or in a small group. Some people may like to try a few different activities to see what suits them best.

Gardening

Gardening is a great physical activity that provides the opportunity for a person to get outdoors! The level of activity can also be varied dependant on a person’s abilities. A person who requires a low level of exertion could weed or prune, whereas if more strenuous exercise is wanted then raking or mowing the grass.

These sorts of activities can help strengthen the body’s muscles and improve breathing and is an enjoyable activity for people at all stages of dementia.

Seated exercises

A person living with dementia can benefit from a regular programme of seated exercise sessions at home or with a group. It is recommended to see these exercises demonstrated at least once by an instructor or on a video.

Here is a video of a seated exercises program for persons with dementia demonstrated by McCormick Care Group:

These exercises are aimed at building or maintaining muscle strength and balance are less strenuous than exercises in a standing position. They can be part of a developing programme, with the number of repetitions of each exercise increased over time.

Swimming

Swimming, under supervision, is a good activity for people with dementia and many find the sensation of being in the water soothing and calming. Some studies have also shown that swimming may improve balance and reduce the risk of falls in older people.

Walking

Walking is suitable for all activity levels as the distance and time spent walking can be varied. Some organisations and local leisure centres arrange group walks supported by a walk leader.

Bariatric moving & handling- challenges and solutions

The moving and handling challenges presented to carers and professionals when supporting their bariatric patients can be considerable and numerous, depending on the environment they find themselves in and the relative weight of the individual requiring support. This article does not aim to be an ultimate resource for those looking for all solutions bariatric, rather as a signpost for points to consider and potential solutions. This article will discuss the following points: biomechanical forces, dignity, the fallen person & hoisting.

However, what is meant by the term bariatric? This term derives from the surgical profession as a method of identify persons categorised over a certain weight. The rule of thumb for guidance is usually any person with a BMI of 40 or above or 300 lbs (Cambridge dictionary 2020). However, as we will discuss the weight is not the only problem that causes problems with moving and handling, but the body shape and size relative to that. Therefore, we have other terms such as “a person of size” or “plus sized”, that are also used to describe those historically referred to as “Bariatric”. The following segment on biomechanics will discuss this further.

Biomechanics in moving and handling

Understanding the basics of biomechanics in moving and handling is key, especially when justifying often costly equipment to managers who are often lay people, or not inducted to the complex world of moving and handling. The main principle we will concern ourselves with is the principal of force. Explained very quickly; if you need to move 100lbs in weight, you will require more than that number to be able to move it. This basic principle come from Newton’s second law of motion (Khan Academy 2020). Therefore, for example if you have a 320 lb person collapsed on the floor and they are unable to get themselves up and require help to do so, they will need a force greater than 320lbs in lift to achieve that. This does not consider displacement of the weight. Similarly, when moving that same weight across a surface such as a room, in a mobile hoist, the same rules applies with the added friction of the hoist meeting the floor. Again, a person may not be deemed bariatric however their body shape might mean getting access to the person to assist safely or friction between themselves and surfaces, such as the side of chairs, may also increase biomechanical resistance.

Dignity

Often when supporting our bariatric patients, to counter the biomechanical forces required to move them, for example to support them with personal care, can often require many carers. This can leave clients feeling exposed and vulnerable, not a dignified position to find yourself in. It is important that we understand this and do what we can to allay concerns and attend to support their dignity as far as is possible.

Discuss with your client in advance your plans, what are their thoughts, concerns and wishes in that regard and how you can work together to achieve the handling aims, whilst taking into account your patient’s thoughts.

The fallen person

People fall for a variety of reasons, trips, slips, medical reasons, however if they are unable to assist in any way to get themselves up, we have to have available resources to enable this, and this to be done safely. Consideration of the client’s weight, dignity and safety of the individuals potentially supporting the fallen person are all equally important. Paramedics and care home personnel often find themselves in this situation where they are required to support a fallen person. However, with a bariatric person this is complicated by the amount of force that has to be counteracted and potentially need for them to lift themselves up, is likely greater than they have the strength to manage, requiring outside help. One potential solution for this is a Mangar Elk (Mangar health 2020). This Is a series of connected inflatable cushions that can be placed under a fallen individual and inflated gradually cell by cell. This allows carers to support the client posturally without having to manage the entire or majority of the patient’s weight, reducing the risks associated to all parties. These can be stored very easily in cupboards and are used widely by paramedic services in the UK for exactly that reason. With a maximum load weight of 980 lbs and easily stored they provide a very flexible and easy to store potential solution.

Hoisting

General hoisting is often compounded by the fact that bariatric patients create more biomechanical force when being moved. Hospitals and care homes often have policies which reflect a need for risk assessments to ensure wards and departments have the personnel on hand to turn a person for personal care for example. Mobile hoists can be purchased that have adequate safe working loads to lift a person from the bed for example to a special chair. The challenge arises due to the biomechanical force being created. In the case of a mobile hoist, it is not just the weight of the person being lifted out of bed for example, but the amount of friction being created by the weight of the hoist and the patient acting against the surface of the floor. In circumstances such as these hospitals, care homes and private residences generally opt to have specially designated rooms with ceiling track hoists (CTH) installed. If not installed when the building is being built or designed often need to be supported by a structural engineer at the planning stage, to ensure the building does not need to be reinforced.

A CTH works by significantly reducing the forces not just in lifting the patient but moving them from surface to surface, for example, from bed to chair. The CTH removes the friction caused by the weight of the person against the floor. The CTH can also have a motorised carriage making moving the person even easier. This can potentially reduce the number of care staff required at every call to support a person, due to the reduced strain and effort now required.

In conclusion therefore working with bariatric patients can lead to challenges in maintaining their dignity whilst being moved and counteracting the large biomechanical forces to be able to move them. However, through good communication we can improve a person’s dignity, and via modern handling equipment such as the Mangar Elk or CTHs we can counteract the biomechanical forces making it easier and safe to move them.

Reference list

Cambridge dictionary (2020) definition of bariatric. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/bariatric

Khan Academy (2020) What is Newton’s second Law.2020 Khan Academy https://www.khanacademy.org/science/physics/forces-newtons-laws/newtons-laws- of-motion/a/what-is-newtons-second-law

Mangar Health 2020 Mangar Elk https://mangarhealth.com/uk/patient-lifting/at-home/elk-lifting-cushion/

When the Inflatable Lifts Replace Bended Backs

Introduction

This project takes as its starting point the fact that approx. 1,700 times every year, an elderly citizen in the City of Copenhagen falls in their home and cannot get up again without help. Employees in home care are called out to these falls, but it is often also necessary to summon assistance from the fire brigade.

This has meant that citizens have often had to lie on the floor for more than 1 hour before help arrives, as the fire brigade’s main tasks are emergency, life-threatening events.

A pilot project looked at opportunities for new technological solutions to the problem and discovered new possibilities to rethink the task so that the use of the fire brigade could be reduced and thereby also the waiting time for both citizens and employees.

This resulted in two mobile lifts being tested in two home care units in 2008. The pilot project showed that the changed work routines that resulted from the introduction of the new tool, not only provided a better but also a more effective solution to the task and a better working environment for the employees.

Helping up older people who have fallen

The background for a project that focuses on developing and testing the equipment is that it is typically moving the position from lying to sitting that is most difficult for the citizen, and which represents the major occupational strain for the carer, as this involves ‘dead weight’ when citizens cannot do anything themselves to help.

It must first be emphasised that the circumstances of each case are always unique. But there are two characteristic working procedures:

- A citizen calls on their emergency alarm when they have fallen and cannot get up. The Homecare Service sends out two employees, one of whom is from the nursing group.

- A carer comes on a scheduled visit to a citizen and discovers that they have fallen. If the carer cannot guide the citizen, they call the Homecare Service and summon assistance. If the carer is in the slightest doubt about whether the citizen has been injured, the assistance shall be provided by a nurse.

Due to the potential occupational strain from lifting a citizen up from the floor, the working environment instructions are that the employees must initially try to guide the citizen up so that the citizen can get from the floor to a chair or bed by their own efforts. In those situations where the employees cannot guide the citizen up, the City of Copenhagen has an agreement with the fire brigade that they will be called for assistance.

Project goal and labour-saving potential

The goal of the project was to optimise the working procedures of the Homecare Service by introducing mobile lifts as permanent aids.

Before the start of the project, the Homecare Service used an average of 150 minutes on the falls where employees could not guide the citizen up and had to summon assistance from the fire brigade. It was expected that by having mobile lifts available, the Homecare Service would be able to solve the same kind of falls in 2 x 25 minutes with two employees (50 minutes in total).

Since there are 1,700 falls every year, where the employee cannot guide the citizen up, the anticipated time-saving potential in the City of Copenhagen was approximately 5.2 FTEs or DKK 1.6 million annually.

The project was also expected to have a number of positive side-effects, such as an improved working environment and improved citizen services. This is because the introduction of the mobile lifts would entail a more gentle lifting procedure for both the citizen and the employee.

Success criteria

The project is designed around the achievement of the seven criteria for success:

1. The labour-saving potential.

By introducing the technology of mobile lifts, there is a proven savings potential for homecare in the City of Copenhagen of approx. 5.2 FTEs or DKK 1.6 million annually.

2. More falls can be handled without using the fire brigade

There is an increase in the number of fall situations that the home care service can handle without using the fire brigade.

3. The employees’ perspective

The employee experiences a more caring handling of the task “Up from the floor after a fall” through the use of the mobile lift technology. The employees experience a labour-saving potential as positive.

4. The citizens’ perspective

The citizen experiences a more caring handling of the task “Up from the floor after a fall” through the use of the mobile lift technology.

5. The organization

There is a successful organisation in relation to storage, transportation and maintenance of the mobile lift technology.

6. The training

The relevant home care employee completes a training course in the use of the mobile lift technology in the form of an introductory course, on-the-job training and a general introduction to techniques for moving people.

Technology

The pilot project had demonstrated that the employees were open to the use of a mobile lift and to solve the task themselves. But it also became clear that it was very important that the mobile lift was reliable. If the employees felt that they could not rely on the lift, they chose not to use it from the outset.

Based on a number of qualitative and quantitative requirements, it was decided to purchase mobile lifts of type Mangar ELK.

The ELK is an inflatable lifting cushion that allows two employees to lift a citizen of up to 450 kg from the floor without straining the employees’ backs. The seat height of 56.5 cm means that when the cushion is inflated, the citizen can get up by themselves (or with support from the employees) and stand by their walking frame, sit in a chair or on a bed.

The ELK weighs a total of 9.7 kg and consists of a 5-compartment lifting cushion, a compressor and a hand control. The four cushions are filled with air from a small portable compressor. As the compartments fill with air, the citizen is lifted up until they are at a height where the employee can move them without straining their back.

The pilot project had shown that the most suitable solution was to place the mobile lifts in the Homecare Services nursing cars. Since a qualified nurse’s assessment is required in fall cases, this ensures that the lifts can be quickly deployed at the citizen who requires assistance to get up off the floor after a fall. It was considered that the requirement would be covered if each homecare unit was equipped with 3 mobile lifts each.

Data basis

The evaluation was conducted by Arbejdsmiljø København [Working Environment Copenhagen] and provided an overall impression of the impact of the introduction of the mobile lift on homecare.

The evaluation is based on qualitative and quantitative data collected from six different sources:

- An evaluation workshop

- Participant observation

- A limited registration of the use of mobile lifts

- Collected data on the use of the Copenhagen Fire Brigade.

- Analysis of selected parts of the City of Copenhagen’s satisfaction measurement

- Interview with the 2 instructors from Arbejdsmiljø København

Results

Success criterion 1: The labour-saving potential.

By introducing the technology of mobile lifts, there is a proven savings potential for home care in Copenhagen Municipality of approx. 5.2 FTEs or DKK 1.6 million annually.

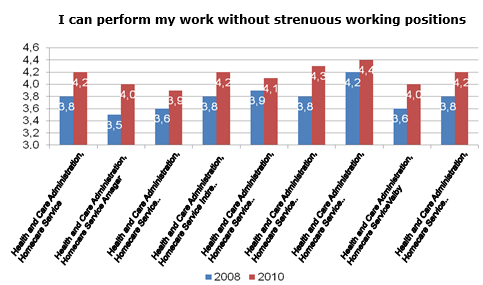

It was expected that by having mobile lifts available, the homecare service would be able to solve the same kind of falls in 2 x 25 minutes with two employees. It takes two employees to help a citizen up from the floor with a mobile lift after a fall. The evaluation showed that on average, 2 x 22 minutes were used by two employees.

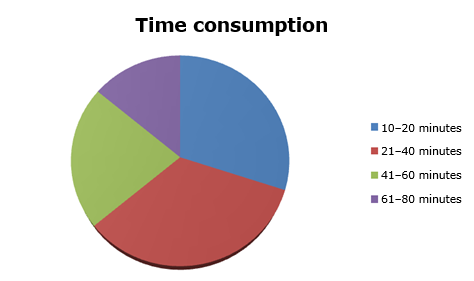

The recording of falls in the two home care units and in the 24-hour service (Døgnbasen) showed that the total time used by the two employees ranged from 10 to 80 minutes. The large variation may be explained by the fact that there are major differences between the extent to which the citizens can cooperate, and how long it, therefore, takes to get the citizen standing by their walking frame, sitting in a chair or lying on a bed.

The baseline measurement showed that before the start of the project, the homecare service used an average of 150 minutes on the falls where the employee could not guide the citizen up and needed to call for assistance from the Fire Brigade.

Since there are 1,700 falls every year, where the employee cannot guide the citizen up, the time-saving potential in the City of Copenhagen was approximately 5.6 FTEs or DKK 1.85 million annually. ((method: 1,700 falls x 106 minutes/940 hours average annual citizen time per employee (average for social and healthcare worker and nurse)) x (1940 gross annual norm per. employee/940 hours) x (DKK 170 average hourly wage from fldnet.dk) – (1 FTE for practical organisation)).

Success criterion 2: More falls can be handled without using the fire brigade

There is an increase in the number of fall situations that the home care service can handle.

The Homecare Service entered into a new cooperation agreement with the Copenhagen Fire Brigade in July 2009. The purpose of the agreement is that the Homecare Service shall have the necessary assistance from the Copenhagen Fire Brigade in connection with citizens who have fallen in their own homes.

The service is limited to cases where the citizen has fallen in their own home and where the Homecare Service cannot help them to their feet again. Even when the Fire Brigade has arrived, the homecare service is responsible for the citizen and cannot leave the citizen, even after the Fire Brigade has arrived.

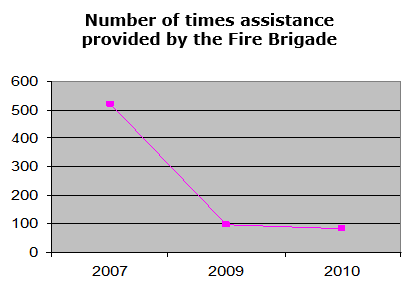

In 2007, the Copenhagen Fire Brigade was called to assist in 520 cases of falls in citizens’ own homes. This dropped to 96 trips in 2009 and an estimated 84 trips in 2010. The registration survey showed that in only 4% of the falls where the mobile lift was used was it necessary to give up and call for assistance from the Fire Brigade.

The reason that there was a significant decline already in 2009 is that there was confusion in relation to a new agreement from September 2009. Here, a number of employees had mistakenly believed that they could not summon the Fire Brigade, but should deal with all falls themselves.

The figures for 2011 onwards are likely to be even lower in step with the mobile lifts being fully integrated into the daily routine and especially when there is a satisfactory solution to the problem that the mobile lifts are viewed as heavy and awkward to transport.

Assuming that the number of falls requiring assistance remains constant, a decrease from 520 trips in 2007 to an estimated 84 trips in 2010 indicates that assistance from the Fire Brigade was only required in 16% of the cases. Since the target was 15 %, it must be concluded that the project has achieved its goal.

Less psychologically stressful cooperation

The evaluation shows that the Homecare Service’s increased opportunities to help a citizen up after a fall is perceived as an improvement of the psychological working environment.

There have previously been many cases where employees felt that the firemen who were summoned, questioned whether there really was a need for assistance. This was perceived as psychologically stressful, which reinforced the feeling of helplessness that many employees experienced when they had been forced to let a citizen lie on the floor for a longer period because they could not guide them up.

“One of the best things has been that we no longer have to deal with angry firemen” (Employee in the Homecare Service)

“We do not have to deal with the same conflicts when we call the Fire Brigade now, because we can say that we tried ourselves” (Employee in the Homecare Service)

Success criterion 3: The employees’ perspective

The employee experiences a more caring handling of the task “Up from the floor after a fall” through the use of the mobile lift technology. The employees experience a labour-saving potential as positive.

For the employees, the labour-saving potential was only of minor importance for their positive perception of the mobile lifts.

The time aspect has a more concrete and practical significance for the employees. Firstly, time plays a role in relation to named irritation over the long waiting time for assistance from the Fire Brigade. Secondly, it is significant because it is in the nature of things that it is impossible to predict when a fall will occur, and it is an urgent task. There is a major risk, therefore, that the longer the task takes, the more it will interfere with the other tasks in a busy schedule and this increase stress levels.

“The ELK results in fewer changes to the schedules. (Group Leader)

For the employees, however, it very important that the mobile lifts are aids that facilitate their work in relation to a very specific and difficult task. They experience the mobile lifts as a useful tool.

“It is quite difficult to understand that we have not always had it. It is a natural part of the work.” (Employee)

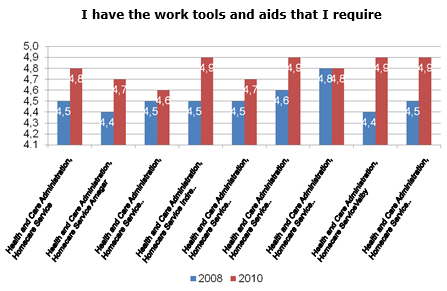

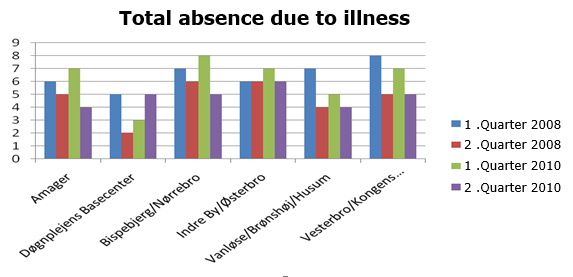

If we consider one specific question in the City of Copenhagen’s job satisfaction surveys from 2008 and 2010 respectively, “I have the tools and resources I need”, we see a clear, positive development in all the home care units. The increase is between 0.1 and 0.5 percentage points.

It is experienced as very positive that the employees have new options in terms of helping an individual who has fallen.

“We are very pleased with the ELK and so are the citizens. They can get up without any pain and stand up spontaneously from the ELK” (Employee)

The employees explained that it is of major importance to them that they can do the job themselves: That they can help the citizen all the way up, make sure that the citizen is well and then move on to other tasks – instead of having to sit and wait for up to one hour for assistance. It gives them a sense of authority and competence in performing their tasks.

It requires a certain amount of practice and good cooperation between the two employees to lift a citizen successfully with a mobile lift. One employee prepares the cushion and the compressor, while the other talks to the citizen, explains what will happen and ensures that there is a chair or a walking frame ready for the citizen to use.

Together, the two employees get the citizen onto the cushion, possibly by using a slide sheet. One employee operates the mobile lift, while the other stands behind and supports the citizen. When the citizen is up and placed in a chair or bed, the mobile lift is cleaned with spirit and packed into the bag.

Proper use of the mobile lifts requires that the employees can communicate with the citizen. It is difficult if the citizen is very confused, intoxicated or otherwise unable to cooperate. This can sometimes mean that the task must be abandoned and the Fire Brigade is called.

The only recurring criticism in relation to the use of the mobile lifts is that it is perceived as heavy and awkward, especially when it has to be transported up to e.g. the fifth floor. For some employees, the difficulty of transporting the mobile lift became an excuse for not accepting the new tool.

“I’m not so big, and I think it is difficult to carry. So I must admit that I don’t take it up with me often enough if, for example, it is a fifth floor apartment and I know that the staircase is narrow” (Employee)

The producer is developing a prototype in a backpack as a solution to the transport problem. This has occurred through input from e.g. the Homecare Service.

The evaluation shows very clearly that employees have experienced that the implementation of mobile lifts as a work tool has reduced both the physical and the psychological working environment impacts associated with helping a citizen up from the floor after a fall.

“The back pains are not as bad as before. You could get really tired after a long night.” (Employee)

The physical strains occur when the employees try to move the citizen off the floor. Transfer from the floor represents a particular strain on the body because it is impossible to keep the spine in its natural, neutral position or to avoid twisting and bending the back during the transfer.

The psychological stress arises partly as a result of the stress and helplessness experienced as a result of being unable to help a citizen out of an unpleasant and undignified situation and having to wait a long time for assistance from the Fire Brigade. But stress also occurs when other scheduled tasks have to be postponed at short notice in order to deal with an emergency situation.

In addition to the mobile lifts reducing the actual occupational work load, it also affects the working environment in a more indirect way, by focusing on the potential stress inherent in transfer tasks. This occurs because the use of an aid like a mobile lift helps to make employees aware that it is a transfer task that strains the body.

“There is a greater understanding among the employees of the importance of transfers and prevention” (Working environment manager)

However, one should be aware that the use of a mobile lift may in itself cause strain on the body because the employee must transfer the citizen from the floor onto the cushion of the mobile lift.

“This can be difficult because one has to kneel down and take hold of the citizen who is on the floor” (Employee)

In addition, some employees find it a burden having to transport the mobile lift up the stairs:

“Nurses have a sore lower back after carrying the ELK from the car, along the street, and up to the third floor and by standing in an inappropriate position while the device is operated.” (Working environment representative)

It is generally believed that the use of mobile lifts has had a positive effect on the number of occupational injuries. It has not been possible to see whether this is reflected in the reported injuries.

It is generally believed that the use of mobile lifts has had a positive effect on the number of absences due to illness. However, it has not been possible to see whether this is reflected in the statistics compared with the first two-quarters of 2008 and 2010 respectively.

Success criterion 4: The citizens’ perspective

The citizen experiences a more caring handling of the task “Up from the floor after a fall” through the use of the mobile lift technology.

The citizen is made to feel safe by the fact that the employees can reassure the citizen, tell them what is going to happen and support the citizen during the lifting. It is also of great importance that the citizen can quickly get out of a situation that is uncomfortable and undignified.

“People had a pleasant “up from the floor” experience – it is very calm” (Employee)

Some citizens experience the situation of using a mobile lift as cumbersome and slow because, after all, it takes time to deploy the mobile lift and pump up the four cushions. They have difficulty understanding why the employees do not just lift them up. However, this is an issue that was even clearer when they had to wait for the Fire Brigade.

“Some say – can you not just take hold here and help me up?…” (Employee)

It requires a certain degree of cooperation by the citizen to use the mobile lift. The citizen must be able to communicate with the employee and must have some ability to balance so that they can sit on the cushion during lifting. This means that if the citizen is very confused or intoxicated, the employee must give up and call the Fire Brigade.

This problem could be solved by the Homecare Service supplementing the model of mobile lift used in this project with a larger model that also has a back and armrests. It should be noted here, however, that this would probably be somewhat heavier than the mobile lift used in this project.

“She was very drunk and it was difficult to determine how much she understood. It would probably not have worked if we two had not known each other well” (Employee)

It has not proved useful to prepare the planned information material for citizens about the technology and about the citizen’s role in the use of mobile lifts. The fall situations are often experienced as being unique, where it is the direct communication between the citizen and the employee that is decisive.

“The citizen was very pleased with the ELK, even though it was a new experience for them” (Employee)

Sometimes, the situation involves citizens who would have very little benefit from written information. However, one can imagine that if the idea was implemented to place a mobile lift permanently in a home where the citizen falls frequently, it would be appropriate to provide more formal information.

Success criterion 5: The organisation

There is a successful organisation in relation to storage, transportation and maintenance of the mobile lift technology.

The organisation and administration of the mobile lifts have quickly become an integral part of each home care unit’s daily operations and therefore also reflect the differences that exist between the organisation of the various units.

In some units, all three mobile lifts are placed in the nursing cars, while in others only two lifts are placed in cars, while the third is stored with the nursing manager. Placing the lifts in the cars is due to the fact that in the City of Copenhagen, it is the normal practice that a nurse will be summoned in case of a fall. The nurse uses a car as the means of transport, since there may be long distances between those who receive nursing care. The mobile lifts are therefore stored in the car permanently.

Because the homecare units have more than three cars each, some coordination is also required. However, the evaluation shows that this does not cause problems.

“The others know that I have the ELK in the car. So they cover for me when I need to deal with a fall in their area” (Employee)

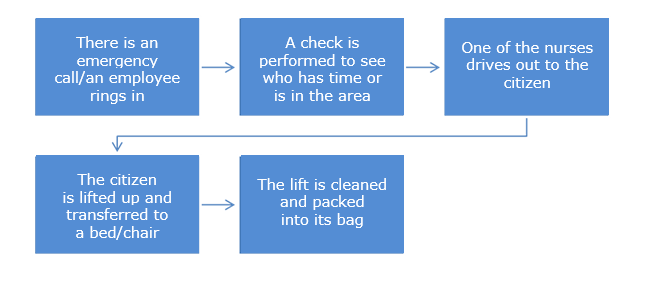

A generalised outline of the working routine could look like this:

It was estimated in the project application that a total of one FTE would be used in the entire Homecare Service for the administration of the mobile lifts. It has not been possible to record the specific amount of time spent on the administration of the mobile lifts because, in step with the implementation, it has become an inseparable part of the general administrative work around the use and maintenance of aids. But the evaluation discovered no expressions of irritation that the implementation of the mobile lifts was an additional administrative burden on the homecare units.

The small amount of time spent on administration was also thanks to the fact that the ELK was very reliable (unlike the mobile lift used in the pilot project) and it was therefore only necessary to contact the manufacturer on a few occasions.

“There is very rarely anything wrong. But otherwise, the way it works is that those who have used the ELK are also responsible for reporting back if there are any problems” (Team leader)

Success criterion 6: The training

The relevant homecare employee has completed a training course in the use of the mobile lift technology in the form of an introductory course, on-the-job training and a general introduction to techniques for moving people.

Good instruction in the use of a new aid minimises the risk that the employees shied away from using a mobile lift, either because they did not feel competent or because they did not appreciate its potential.

The specific target group for the courses was mainly the resource persons for transfer in the Homecare Service and the 24-hour service who perform the task in relation to falls and who are in direct contact with the citizens in case of a fall. The knowledge they acquired about using the mobile lifts could be used both in their own work and for the instruction tasks they have in the individual homecare units.

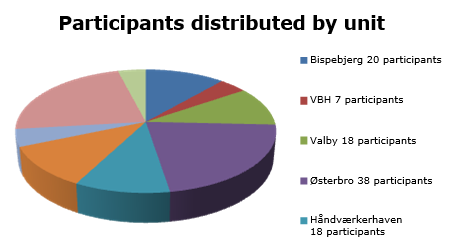

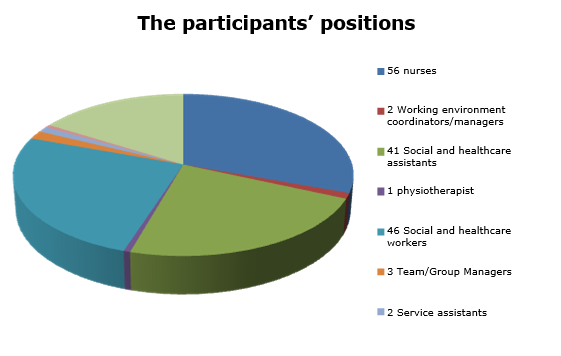

A total of 178 employees participated in one of the 9 courses. All the homecare units participated, but with very different numbers of employees. This was primarily due to the different ways of organising the training locally. The employees were divided between all the different professional groups:

The course lasted 3 hours and was conducted in Arbejdsmiljø København’s “bed ward”.

The teaching was divided between practical training in the use of mobile lifts and more general training in transfer techniques.

The practical training was designed to instruct personnel in the use of the equipment. The course participants were familiarised with the mobile lift and they worked with it so they became comfortable using it. At the same time, they had an opportunity to give their immediate reaction to the mobile lifts and could suggest improvements. Those who had used a mobile lift in practice were able to talk about their experiences.

“It’s very effective when some of the course participants can tell the others that it is a good tool” (Instructor)

When the employees are comfortable with the use of the lift, there is less risk that they return to lifting the citizen or calling the fire brigade unnecessarily. Finally, the employees’ confidence reassures the citizen, so they are not “afraid” of the new, unfamiliar methods.

The overall training in transfer techniques provided the course participants with knowledge about transfers at floor level. They have learned about working posture and methods to avoid the most stressful postures and movements.

“It is very important that the employees receive structured instruction in the use of a mobile lift and get an opportunity to try it. Otherwise, there is a risk that it will end up unused in a corner.” (Instructor)

The employees experienced the training as very meaningful and fruitful. They have subsequently been able to train their colleagues at local, joint weekly group meetings so that they all became qualified to operate the mobile lifts.

The instructor’s assessment is that the training could have been cut down to two hours, without affecting the quality.

Success criterion 7: The technology

The project used a tender process to ensure the best private partner in relation to the economy, quality, technology development possibilities, service, etc.

The tender process was completed without any problems. Based on lessons learned from the pilot project, it was possible to establish clear technical and qualitative requirements for the lifts and to select the most qualified product called the ELK.

The tender documents emphasised that the mobile lift should be able to perform the task ‘up from the floor after a fall’ by lifting a person from the floor level to a height of at least 55 cm.

It also included a number of requirements based on the needs of the employees:

- Low lift of total weight (maximum 5 kg/10 kg.)

- Low total weight (maximum 10 kg.)

- Can be used with both electricity and battery

- It should be easy to clean the lift

- It should be easy to transport the lift (even climbing stairs)

- It should be easy to instruct new users in the use of the lift.

Finally, two requirements were based on the needs of the citizen:

- High user weight (minimum of 250 kg.)

- The citizen should feel safe while being lifted.

There were two suppliers who submitted offers, but only one could meet the requirements. A contract was concluded with that supplier. The contract has no set term but runs initially for one year and the lifts are then expected to be included in the general municipal operations.

Summary

The project fully met its goal. It has proved possible to optimise the working routines by the Homecare Service’s employees themselves using mobile lifts to help citizens up off the floor after a fall, instead of having to wait for assistance from the Fire Brigade.

The optimised working routine is estimated to free up labour corresponding to 5.6 FTEs. This is 0.4 FTEs more than the estimated labour-saving potential.

Before the start of the project, the Homecare Service used an average of 150 minutes on the falls where employees could not guide the citizen up and therefore had to summon assistance from the Fire Brigade. It was expected that by having mobile lifts available, the Homecare Service would be able to solve the same kind of falls in 2 x 25 minutes with two employees. The evaluation showed that on average, 2 x 22 minutes were used by two employees.

The project included a 3-hour course conducted by Arbejdsmiljø København for the resource persons in transfer in the home care unit and the 24-hour service that performs the task in relation to falls. These people subsequently trained their colleagues. A total of 178 employees, distributed between all the home care units and the 24-hour service, participated in one of the 9 training sessions.

Falling Into Fear Of Falling

Around a third of people aged over 65 and a half of people aged over 80 fall each year1.

Fear of falling is a common term used in healthcare2, with patients asked “Do you have a fear of falling?” and a score often attributed to it3. 50% of people who have fallen and 50% of people who haven’t fallen are affected4. When you think about it though, it would be a bit unusual to find someone who didn’t have a ‘fear of falling’ – after all, who would be happy if they fell over? If someone told me I was going to fall over this week, it would definitely be on my mind. What we really want to know is whether someone has a fear of falling to the degree that it stops them from doing things, such as walking around the home or going outdoors.

Two main things are likely to influence our fear of falling: how likely we feel that it is that we are going to fall, and if we do fall, how bad the consequences will be. Essentially we are performing our own risk assessment of our mobility which will then influence our behaviour. If I felt there was a high chance that I was going to fall during an activity, I’d think twice about doing it. Likewise if I believed that I would significantly hurt myself if I fell, I’d think twice about doing it. If I felt there was both a high chance of me falling, and it would likely result in me significantly hurting myself, I would be unlikely to do it. As a 33 year old with no underlying medical conditions I do not feel that it is likely I will fall when I’m walking, or that I would hurt much more than my pride if I did fall, so falling is not on my mind and doesn’t stop me from walking. However, send me ice-skating and it’s a different story: I would have a high fear of falling and adapt my behaviour accordingly, likely by holding on tightly to the rails and going very slowly, or choosing not to take part at all. My fear of falling will have increased.

The highest risk factor for falling is having had a previous fall5, which can often cause an increase in fear of falling and altered behaviour. I was running along a muddy coast path a few years back when I slipped and fell, landing on my head. Fortunately, it was just soft muddy grass I landed on, so I got up and carried on. For the rest of the run though I was much more concerned about falling, and I ran a lot slower holding on to trees for support until my confidence returned. But imagine if you had reduced strength and balance, and essentially viewed just walking around your home as going on the ice rink or slippery muddy path. Add to that an experience of maybe having fallen last month and fracturing your wrist or hip. It would be understandable to lose confidence in mobilising and be worried about moving around much incase you fell again. This is something I witnessed multiple times both on hospital wards and in the community working as a Physiotherapist: Someone falls, with or without injury, they lose confidence, and so stop going out or walking much in order to reduce their risk of falling again.

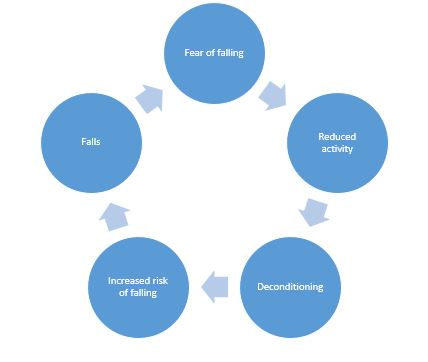

The problem with this though is that by becoming less physically active in order to reduce the risk of falling whilst up and about, you are actually increasing your risk of future falls. Falls can lead to fear, and fear can lead to falls. This is because of a process called deconditioning, which has become a strong focus in healthcare recently through campaigns such as #EndPJparalysis5. Deconditioning is a process whereby physical ability deteriorates due to lack of activity6, with muscles becoming weaker, fitness decreasing and a reduction in balance. ‘Use it or lose it’ is a well-known expression, and when it comes to our physical abilities it’s true. Over time inactivity can lead to weakness and decreased mobility, which can lead to an increased risk of falling. This can create a vicious cycle of falling, increased fear of falling, and inactivity:

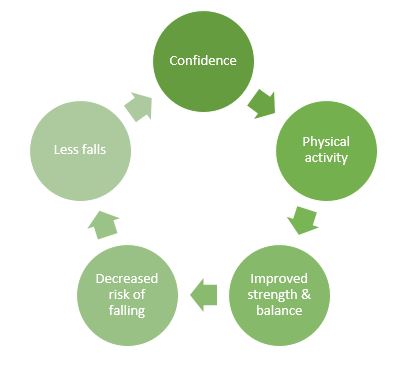

Once in this cycle it can be hard to reverse it. It is important to encourage and enable physical activity via effective strength and balance activities7, as part of a multifactorial assessment and intervention, to tackle deconditioning, in order to improve confidence and reverse the cycle:

Multifactorial falls risk assessments can reduce falls by 24% and should be offered to all older people who have fallen or are at risk of falls1. By acknowledging the fear of falling and the associated consequences, we can help prevent people from falling into fear, and that fear leading to falling.

Written by Oliver Williams, a Physiotherapist and Speciality Registrar in Public Health, Wales

Reducing Musculoskeletal Injuries In Care Facilities

It has been stated that “The adult human form is an awkward burden to lift or carry. Weighing up to 200 pounds or more, it has no handles, it is not rigid, and is susceptible to severe damage if mishandled or dropped. When lying in a bed, a patient is placed inconveniently for lifting, and the weight and placement of such a load would be tolerated by a few industrial workers”.[1]

Providing care in any nursing or residential facility is can be physically demanding work. Patients or residents often require assistance with transfers, personal care (including bathing & showering), mobilizing and other daily activities that can compromise the physical integrity of the carer.

Carers are often in situations that encourage poor posture (such as bending, stooping and reaching) with further negative reinforcement by the force required and repetition of the tasks. Indeed research in 1988 determined that back pain accounted for 25% of all workers compensation claims in the US with 22.4 million cases equating to 149.1 million lost workdays.[2]

In 2003 (revised 2009) the United States Department of Labor issued a guidance document titled ‘Guidelines for Nursing homes: Ergonomics for the prevention of musculoskeletal injuries’.[3] In this document the Occupational Health & Safety Administration recommended that to reduce risks all employers should:

- identify problems;

- implement solutions;

- addresses reports of injuries;

- provide training

They go on to suggest that ‘when problems related to ergonomics are identified, suitable options can then be selected and implemented to eliminate hazards. Effective solutions usually involve workplace modifications that eliminate hazards and improve the work environment…usually including the use of equipment…’

Interestingly the document provides some valuable decision-making algorithms and diagrammatic equipment options to resolve certain situations without mentioning the fallen resident or any solutions for handling in that circumstance.

It is reported that 33% of all musculoskeletal work-related injuries occur as a result of patient handling activities, with 83% of those injuries from in-patient healthcare workers. It is suggested that 40% percent of injuries due to lifting/transferring patients may have been prevented through the use of mechanical lift equipment.[1]

When considering equipment used to reduce or eliminate risk there is a challenge to understand, appreciate and reflect on market changes or technological advances. What was an appropriate piece of hoisting equipment 20 years ago may no longer be the most efficient or risk-reducing?

Theory and evidence also change on the basis of new research or experiential clinical reasoning which not only affect the choice of equipment but also processes and risk assessment. For example, our understanding of the ‘long lie’ and ‘delayed initial recovery’ research following a fall enables us to consider the equipment that safely supports positional change within ten minutes of the incident (fall). This alongside evidence regarding dignity and respect following a fall may determine us to consider that full-body passive hoisting from the floor may not be the most effective solution in terms of recovery.

An example of this developing evidence is the research conducted regarding the use of ceiling track hoisting systems:

‘A longitudinal study was conducted in three long-term care facilities to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-benefit of overhead lifts in reducing the risk of musculoskeletal injury among healthcare workers. Analysis of injury trends spanning 6 years before intervention (1996-2001) and 4 years after the intervention (2002-2005) found a significant and sustained decrease in workers’ compensation claims per number of beds and in working days lost per bed. The payback period was estimated under various assumptions and varied from 6.3 to 6.2 years if only direct claim-cost savings were included, and from 2.06 to 3.20 years when indirect savings were added’.[2]

Similar evidence can be found regarding supporting someone from the floor following a fall, where work in the United Kingdom has demonstrated a significant reduction in musculoskeletal injuries for paramedics called to help someone in a domestic setting.[3]

To proactively reduce musculoskeletal injuries as a result of patient/client handling a commitment must be made in some critical areas:

- Investment – Initial outlay on the right equipment is shown to be recouped quickly.

- Knowledge – Professionals and commissioners must be aware of up-to-date research to support evidence-based decision making.

- Market – There must be a commitment to know the equipment market so that informed decisions can be made.

- Process – Care facilities must have processes in place to assess, determine and reduce risks that are reviewed fluidly

Ensuring these steps are engrained in healthcare culture alongside an underlying commitment to high-quality patient and employee care will go a long way to reducing injuries and risks to both groups moving forward.

[1] Pompeii LA et al (2009) ‘Musculoskeletal injuries resulting from patient handling tasks among hospital workers’. Am J Ind Med. 2009 Jul;52(7):571-8. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20704.

[2] Statistics and Evaluation Department, Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare, Vancouver, Canada.

[3] https://mangarhealth.com/uk/case-studies/a-solution-to-manual-handling-in-the-workplace

[1] Anonymous. The nurse’s load (editorial). Lancet1965;ii:422–3 Available at: https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/10/4/206#ref-1 Accessed 02/10/19

[2] Guo HR, Tanaka S, Cameron LL, et al. Back pain among workers in the United States: national estimates and workers at high risk. Am J Ind Med 1995;28:591–602.

[3] https://www.osha.gov/ergonomics/guidelines/nursinghome/final_nh_guidelines.html Accessed 02/10/19

How To Reduce Post Falls Syndrome

Written by: Kate Sheehan, Occupational Therapist

A fall is defined as a unintentional move from a higher to a lower level, typically rapidly and without control, approximately 28-35% of people aged of 65 and over fall each year increasing to 32-42% for those over 70 years of age[1] the evidence also confirms that frequency of falls increases with age and with neurological conditions.

Factors that contribute to falls can be categorized into a number of areas; intrinsic, for example impaired balance or gait, a medical diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease or dementia or postural hypotension; extrinsic such as clutter creating trip hazards, poor lighting or inappropriate walking aids and behavioral factors, including wearing poorly fitting shoes, reduced fluid intake or reduced physical activity.

There are a considerable number of complications that can ensue from lying on the floor for a long period of time, for example, pressure sores (often exacerbated by unavoidable incontinence), carpet burns, dehydration, hypothermia, pneumonia, and even death. We are also acutely aware that a fall can result in post- fall syndrome that includes confusion, dependence, loss of autonomy, immobilization and increased mental health issues, including depression, which will lead to a further reduction in carrying out daily activities.

As occupational therapists it is vital that we enable our clients to return to the their everyday activities that they do as individuals, in their families and within their communities to occupy their time and bring meaning and purpose to their life.[2] And therefore being able to review and recommend ways, which enable a person to get up from a fall in a timely manner are essential; this can be achieved in various ways,

- Teaching our clients to get up off the floor following a fall using the furniture around them, the support of a family member or health professional after it is determined there are no significant injuries

- A carer or family member using equipment to assist someone getting off the floor.

- Calling the emergency services.

The later is for occasions where there is an obvious injury or condition that requires medical intervention, the most important thing is to support the person to get up and to start doing things they want or need to do.

A person can be taught to get up off the floor safely, however if someone is falling on a regular basis, equipment can provide an easy and cost effective alternative to calling emergency services.

When recommending the correct equipment to support someone from prone to sitting it is essential we look at 3 key features

Accessibility – the product needs to be small enough to be easy to store and to able to be carried without difficulty by one person.

Easy to use – the product needs to be simple to use, with clear instructions and visual cues to make it quick to put together and therefore reduce the time a person is on the floor.

Confidence and comfort – the product must provide a supportive cushioned seating position to provide comfort and work reliably and quickly to provide the ultimate confidence in it.

The Camel by Mangar, is an inflatable lifting device, which is designed to provide all the key features above. When inflated, the Camel lifts the client into a raised seated position ready to stand with or without assistance. The benefit of the Camel is the client can sit, rest and regain their strength before moving to chair or to walk, thus allowing them to regain their confidence and continue with their chosen activities.

[1] http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf?ua=1

[2] http://www.wfot.org/aboutus/aboutoccupationaltherapy/definitionofoccupationaltherapy.aspx

Doctor Explains The Importance Of Post Falls Assessment Tool, ISTUMBLE

“The reason I became involved with the ISTUMBLE project is that it is so profoundly positive for residents of care homes and those who care for them.

The benefits of lifting a resident off the floor are innumerable. By definition residents of care homes are frail – otherwise, they would not be cared for in a residential context. With frailty comes a lack of physiological reserve and strength. In addition, residents may have multiple co-morbidities involving the major body organs – respiratory/ lung disease, cardiovascular/ heart and vessel disease and renal disease/ impaired kidney function. All these co-morbidities cause reduced skin perfusion. Thus when a resident is kept on the floor for more than 20 minutes the pressure from the floor, especially on bony prominences of the body, further reduces blood supply to the skin. Therefore an elderly person on a hard floor or even a carpet will suffer an early breakdown of skin tissues and ulcer development. The most common complications of skin ulcers are increased mortality, osteomyelitis, and sepsis. If the patient has sustained a femur fracture during the fall the chances of mortality from the pressure ulcer are higher still because the patient will suffer reduced mobility both before and after surgery.

In 20 years of emergency medicine, I have never seen an exacerbation of damage to a broken femur of an elderly patient who has been carefully lifted with an appropriate lifting device.

Other than in the exceptionally unlikely possibility of a neck injury – not lifting the patient who has fallen as a result of any cause I believe is both unacceptable and unkind. As an aside I have never seen a resident of a care home sustain a fracture of neck vertebrae after a fall. I have only seen this from falls of elderly people falling in the street (concrete usually involved).

Of course, should a patient be in cardiac arrest they should not be lifted.

GP’s will not attend patients who are on the floor. Once lifted the GP can visit and thus prevent many trips into busy, loud and excessively lit Emergency departments. Such places are frightening for frail and demented people. Not sending the patient means that care staff is not obliged to travel with the resident preventing attrition of care staff who are needed at the care home.

Finally lifting patients from floors allows carers to continue to do just that – care. Carers become immensely upset to see their residents wait hour after hour on the floor because hard-pressed ambulance services cannot attend. When I have delivered this teaching to care homes there has been overwhelming relief felt by empowered care staff, empowered by education and ability to act.

– Dr Sue West-Jones, a consultant in Emergency Medicine

If you would like to download the free post falls assessment tool, please visit the Apple Store or Google Play Store and search for ‘ISTUMBLE’.

To access the “IStumble” App in the Apple Store CLICK HERE

To access the “IStumble” App in the Google play Store CLICK HERE

Covid – 19: Recuperation and rehabilitation

The term rehabilitation is being used far more frequently in the press recently for good reason, but does everyone understand what it really is?

Rehabilitation is a set of interventions needed when a person is experiencing or is likely to experience limitations in everyday functioning due to ageing or a health condition, including chronic diseases or disorders, injuries or traumas[1]

Typically, occupational therapists working in rehabilitation settings would see patients/clients recovering from a stroke, brain injury, orthopaedic trauma or many other life changing events so we need to understand why this is important for Covid-19 survivors.

What are the long-term effects?

At this stage, just 4 months after the disease was recognised, far more is known about mortality, range of severity of symptoms and early disability, than about the long-term consequences of this condition[2] however we do know that there are a range of presentations and complications (table 1) that impact on long-term recovery and return to pre-morbid health and engagement.

Table 1: Complications in patients recovering from Covid-19[3]

Most frequent Common but less frequent

|

o Stroke o Pulmonaryembolism

syndrome.

|

This information provides a general picture of what some patients recovering from Covid-19 can present with, further highlighting longer-term impacts.

However, with many rehabilitation services commissioned support single conditions such stroke, rather than reflecting need[4], how do occupational therapists not associated with such services ensure that rehabilitation is provided to those who need it, when they need it and where they need it?

Supporting recovery

There will be some people, in particular but not exclusively those with multiple co-morbidities, who find recovery/return to good health a longer-term struggle. There is no ‘silver bullet’ in supporting those patients/clients so it is important to re-evaluate the role that occupational therapists play in rehabilitation generally but with a focus on symptoms and consequences listed in table 1.

Consider the following points:

- It is crucial, as in all areas of practice, to understand what is meaningful to the person in order to support meaningful goals and re-engagement in those activities.

- Consider what purposeful elements impact on the meaningful task so that a graded approach can be supported.

- Rehabilitation plans should be occupation focused.

- Review your approach with an overall rehabilitative goal. For example, you may need to compensate or adapt initially as part of a graded rehabilitation approach. This could include equipment provision, either on discharge or beyond, to support independence and reduce responsibility of others.

- Take care to consider the increased risk of falls during recover for those who are deconditioned. Proactively managing those risks will allow a safer and more effective recover both physically and psychologically.

- As always, consider the impact of the environment on the person and their engagement in activity.

Communication on the benefits of engagement in occupation must be made clear. Now more than ever the public are aware of the impact of reduced freedom to engage in meaningful activity both on their physical and mental health.

The way in which occupational therapists use activity analysis to assess and plan allows meaningful activity to play a crucial role in the multi-disciplinary rehabilitation plan. For example, enabling access to the garden and the activity of gardening itself supports development of exercise tolerance, core/dynamic balance, muscle strength, orientation as well as impacting positively on mood through connection with nature, society and removal from the sick role. Developing these strengths also significantly reduces the risk of falls.

Occupational therapists are going to play a key role in post Covid-19 recovery, and it is important we all remember, regardless of which clinical service we work in, that ‘rehabilitation is not a disability-specific service for those with long-term impairments. Nor is it a service only for people with physical impairments. Rather, rehabilitation is a core part of effective health care for anyone with a health condition, acute or chronic, impairment or injury that limits functioning, and as such should be available for anyone who needs it.’ [5]

[1] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation Accessed 11/05/20

[2] https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/covid-19bsrmissue2-9-5-2020-forweb11-5-20.pdf Accessed 11/05/20

[3] https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/covid-19bsrmissue2-9-5-2020-forweb11-5-20.pdf Accessed 12/05/20

[4] https://www.rcot.co.uk/node/3474

[5] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation Accessed 12.5.20

Protecting EMS Resources During the COVID-19 Outbreak

A UK business that specializes in the supply of safe patient lifting equipment to EMS agencies, has been leading the fight to keep people at home and out of hospital during the COVID 19 outbreak.

Mangar Health manufacture the ELK lifting cushion, designed to lift someone weighing up to 1,000 lbs with the assistance of just one EMT. The company has worked with Ambulance Services for many years and are now supplying equipment to EMS workers serving the new Nightingale COVID Field Hospital in London.

The #stayathome message has galvanised key decision makers in healthcare sectors globally to address the sustainability of EMS services while resources are being severely impacted by COVID 19. Patients being routinely transported to hospitals to be ‘checked over just in case’ is no longer possible. Health assessments in the home and lifting those who have fallen but are uninjured is becoming the norm, thereby reducing avoidable hospital admissions and the pressure on ambulance services.

Pressure on EMS resources because of COVID is already at breaking point (FDNY reported a 23% reduction in workforce due to sickness and quarantine last week) but these key workers face additional risk to their musculoskeletal health daily because of the repetitive nature of manual handling and lifting. The rate of non-fatal injuries among EMTs and paramedics was found to be 34.6 per 100 full-time workers per year, a rate more than five times higher than the national average for all workers in the US.1

Mangar Health CEO Simon Claridge says; “The ELK is proven to reduce the risk of injury to EMTs because when used, very little moving and handling is required to lift the fallen person. The cost associated with musculoskeletal injury in healthcare workers in the US alone is $200 million annually.

“In the UK, The South West Ambulance Service reported a 10% decrease in sickness after introducing the ELK and a saving of $370,000 annually. The statistics clearly demonstrate how safety protocols introduced now, protect workers tomorrow”.

At a time when ET3 is being widely discussed in EMS circles, the British system of treating at home when at all possible makes sense (which is the same as the Treat In Place (TIP) currently proposed as part of the next COVID Stimulus package). At the best of times the elderly are vulnerable to hospital acquired pneumonia and fair better when able to remain in their own home. The opportunity to provide better quality care at home for a lower cost is a concept UK healthcare professionals have recognised and were implementing long before COVID 19.

Maintaining purposeful occupation, fatigue & MS

Just as the word “depression” is often over-used, describing any state of low mood, including temporary lows or natural melancholy, the word “fatigue” has also been over-used. However, unless you have experienced significant, enduring fatigue related to a medical condition, it is difficult to appreciate just how disabling fatigue is. Multiple Sclerosis related fatigue is one of the most debilitating symptoms of the condition, but often the least acknowledged or treated.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, unpredictable autoimmune disease characterized by de-myelinization of nerve cells which results in scarring known as plaques. Common symptoms of MS include vision problems, loss of balance and muscle coordination, slurred speech, tremors, stiffness, bladder problems, cognitive deficits, and fatigue. Like many things, it is easier to provide practical solutions for physical issues related to MS but more difficult to tackle fatigue, which is complex, unpredictable and emotionally and socially embroiled. This is one of the reasons that occupational therapy is the primary profession dealing with MS fatigue.

The strategies for occupational therapists treating MS related fatigue are now well known. Finlayson, Preissner and Cho (2012) note that primary fatigue is often treated by medication but secondary fatigue is helped by a variety of modalities including cardiovascular and strengthening exercises, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and energy management education. Occupational therapists often teach energy management strategies, sometimes combined with elements of CBT, with the aim of managing daily life with fatigue through behavioural change (Matuska et al 2007).

Energy conservation techniques include: changing body position for certain activities; planning the day to balance rest and work; modifying frequency or outcome standards; including rest periods in the day or at least 1 hour; adjusting priorities; simplifying activities; communicating needs for assistance; resting during longer activities; changing location of equipment/supplies; delegating part or all of an activity; eliminating part or all of an activity; identifying and changing incorrect work heights; changing the time of day of an activity; starting to use adapted equipment (Matuska et al 2007). While these strategies make complete sense, there is danger that trying to implement them could add to fatigue, as changing a lifetime of occupational habits, patterns and routines is difficult. Sometimes a sense of failure is all too easy to generate when trying to make significant life changes.

Finlayson et al (2012) reviewed the main OT treatment modalities for MS fatigue but also recognised the factors which affect the outcomes. It’s a great article which explores issues which we know: group treatment is great, but we need to acknowledge find ways of making it effective for all. This came home to me a few years back, when I was involved in a large research project which used cognitive behavioural therapy in a group format, for fatigue management in MS – the FACETS programme (Thomas et al 2013). We were one of the centres which delivered the programme, which had to be followed to the letter. This was a struggle for me as I like to respond to issues that arise and the individual needs of group members. These groups were diverse with participants from all social class groups, genders, ages, work status etc. How people responded to the materials and activities was, as it always is in group work, variable and the benefits that people gained were variable too. The Finlayson research explains why!

However, does measuring the effectiveness of a programme mean that as occupational therapists we are helping our patients develop and sustain meaningful occupations? Not necessarily and if we are not careful we might end up making adherence to treatment guidelines an outcome for treatment, rather than quality of life. We need to consider the “usual” advice we give people and how this might be interpreted and used to best effect, rather than become a possible barrier to occupation. For example, let’s take “pacing” which is often taught in fatigue management, which involves breaking activities into chunks interspersed with rest periods e.g. hoover for 3 minutes, rest for 10, hoover for another 3 minutes etc. We could use pacing with any activities, not just housework, but I am concerned that passion and flow are lost are potentially lost when you pace. What if I start a painting and get so into it and want to paint for hours and that flow and engagement gives me energy. Yes, I might suffer the following day, but maybe that’s the pay-off and maybe I gain more energy from engaging fully? Perhaps that’s a psychological contract I need to make with myself?

Yes, follow the guidelines for fatigue management but as occupational therapists, we must help people figure out what matters to them and ensure they do not lose valued activities. There is often a danger that people exclude their desired activities, in an attempt to save energy on what seems to be necessary such as everyday activities like cleaning, ironing etc. Of course, for some people housework and keeping the home tidy are very important, but perhaps there is room for exploring activities which might increase energy, rather than just use it.

As occupational therapists we need to help people develop self-awareness: who they are, what they love doing, what they need to do and who they want to be in spite of MS and related fatigue. This awareness raising includes helping people evaluate their lives and daily activities with a critical but compassion eye – an eye which is ok with imperfection and small wins. We need to help people identify what activities act as energy drainers and which ones are energy gainers – which activities give us energy or make us feel good, versus which activities leave us tired or unfulfilled. As occupational therapists treating people with fatigue, we need to avoid being technicians and implementors of guidelines and be more like artists, who help people develop a picture of a fulfilled occupational life.

Useful articles and references

Thomas S, Thomas PW, Kersten P, et al (2013) A pragmatic parallel arm multi-centre randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a group-based fatigue management programme (FACETS) for people with multiple sclerosis Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2013;84:1092-1099.

Finlayson M1, Preissner K, Cho C, Plow M (2011) Randomized trial of a teleconference-delivered fatigue management program for people with multiple sclerosis Mult Scler. 17(9):1130-40

Kathleen Matuska, Virgil Mathiowetz, Marcia Finlayson (2007) Use and Perceived Effectiveness of Energy Conservation Strategies for Managing Multiple Sclerosis Fatigue American Journal of Occupational Therapy Vol. 61, 62-69.

Marcia Finlayson; Katharine Preissner; Chi Cho (2012) Outcome Moderators of a Fatigue Management Program for People With Multiple Sclerosis American Journal of Occupational Therapy Vol. 66, 187-197

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene is a behavioral and environmental practice[1] developed initially in the 1970s to focus on insomnia and depression. It considers elements of routine including diet and fluid, lighting, activity engagement, and sleep environment generally to support inducing of higher quality sleep.

Sleep deficiency is a common public health problem in the United States with people in all age groups report not getting enough sleep. As part of a health survey for the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, about 7–19 percent of adults in the United States reported not getting enough rest or sleep every day with nearly 40 percent of adults report falling asleep during the day without meaning to at least once a month. Also, an estimated 50 to 70 million Americans have chronic (ongoing) sleep disorders.[2]

What we need to consider therefore in the first instance is why sleep is important.

The American Sleep Association state that ‘sleep deprivation can lead to many consequences. Without an adequate amount of sleep, our minds and bodies are unable to perform at their peak.’[3] They go on to confirm that there are ‘several potentially bad outcomes that are associated with inadequate sleep. Sleep influences the immune system, memory consolidation, attention, hunger, mood, response time, and many other body functions’.

The impact of sleep can affect children and adults in different ways, simply due to their differing lifestyles and demands but essential elements or reasons are much the same.

For children and adults, a lack of sleep (recommendations range from 14 – 8 hours depending on age)[4] can impact on education, mental health, physical health, and play/leisure

A good night’s sleep is essential for learning new info and remembering it later. This is due to a number of factors:

Enhanced Attention:

If you wake up feeling well-rested, you’ll have greater mental clarity and focus, and you’ll be able to respond faster to questions or stimuli.

Learning Becomes Easier:

If you’re well-rested, you’ll be able to master a new task (like learning how to play a song on the piano) more effectively than if you were sleep-deprived; this is known as procedural memory. During sleep, you also sharpen your declarative memory—your knowledge of complex, fact-based information.

Better Problem-Solving Skills:

After a good night’s sleep, you are more likely to wake up with a more creative idea for a project or how to solve a problem.

Improved Recall:

A sound night’s sleep can help you better remember what you learned the day and speed up your thinking processes

Research even suggests that students at later-starting schools report later rise times, more total sleep on school nights, less daytime sleepiness, less tardiness, fewer attention/concentration difficulties, and better academic performance compared with middle school students at earlier-starting schools.[5]

Sleep and physical health are known to have a bidirectional relationship, where poor sleep is linked to physical health problems but also may be caused by physical health problems. Diabetes, heart function, obesity, and muscle development are all known to be affected by rest through sleep. It is during periods of sleep that the body effectively resets and regulates heart rate and blood pressure.

The same bi-directional relationship can be leveled at sleep and mental health; Take, for example, depression: while a depressed young person may sleep less well and /or have altered recall of sleep duration and quality, they may also be disposed to develop depression because of sleep deprivation. There is a known link between sleep loss and increased suicidality in adolescents which is clearly important to be aware of.

Dr. Sally Hobson, Specialty Community Paediatrician states that Clinicians who are trained to work in mental health settings are well placed to assess and consider sleep problems as part of their formulation. In addition to this systemic thinking, she suggests that any clinician working with children and young people in a physical or mental health/developmental setting should have a basic knowledge of the importance of sleep, of how to take a basic focussed sleep history, talk with